ON EARTH WE’RE BRIEFLY GORGEOUS, a novel by Ocean Vuong, reviewed by Claire Kooyman

Ocean Vuong’s writing is steeped in memories, the history of which sometimes precedes him chronologically. This was true of his poetry in the collection Night Sky With Exit Wounds, and it is also true of his first novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, recently released by Penguin Press. This novel is a recursive exploration of the path memories take through a family. The narrator’s life is impacted by the traumas his mother and grandmother suffered before he was born. As a very young child, Vuong’s narrator, Little Dog, learns quickly that not all authority figures can be trusted absolutely, and that even unconditional love has flaws. Throughout the novel, Vuong illustrates that we are all sharing space with the past, even as we exist in the present.

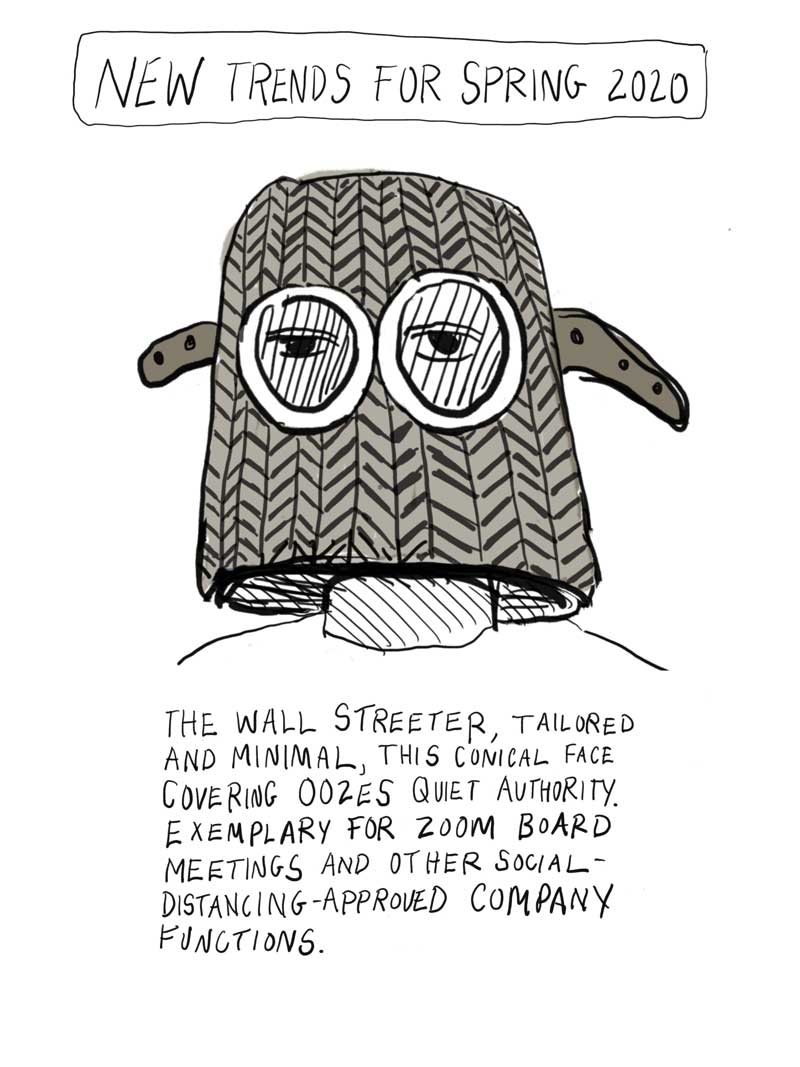

Don't miss Emily Steinberg's take on new trends for Spring 2020 face masks!

Don't miss Emily Steinberg's take on new trends for Spring 2020 face masks!